登录方式

方式一:

PC端网页:www.rccrc.cn

输入账号密码登录,可将此网址收藏并保存密码方便下次登录

方式二:

手机端网页:www.rccrc.cn

输入账号密码登录,可将此网址添加至手机桌面并保存密码方便下次登录

方式三:

【重症肺言】微信公众号

输入账号密码登录

注:账号具有唯一性,即同一个账号不能在两个地方同时登录。

文章来源:中华医学杂志2020年3月3日第100卷第8期

作者:中国医师协会呼吸医师分会危重症专业委员会中华医学会呼吸病学分会危重症医学学组 《中国呼吸危重症疾病营养支持治疗专家共识》专家委员会

通信作者:詹庆元 ,中日友好医院呼吸与危重症医学科,北京100022,Email:zhanqy0915@ 163. com;解立新 ,解放军总医院呼吸与危重症医学科,北京100086,Email:xielx301@ 126.com

近年来 ,针对危重症患者营养支持治疗的临床实施 ,美国危重症协会(SCCM)与美国肠外肠内营养协会 (ASPEN,2016), 欧洲肠外肠内营养协会(ESPEN,2018)等制定的国际指南已发布了明确的推荐意见。而呼吸危重症患者有其疾病代谢和治疗方式的特殊性,有关呼吸危重症的营养支持治疗策略尚无统一的共识和指南推荐。随着临床营养学的快速发展,关于呼吸危重症患者是否可以通过营养支持治疗提高生存率、缩短ICU住院时间、改善患者生活质量等方面的国内外研究日益增多。为求规范呼吸危重症患者的营养支持治疗,国内呼吸危重症和营养学的专家们对相关的循证医学证据进行了系统地检索、筛选、评价 ,包括高质量的系统回顾、 荟萃分析和相关的RCT研究。对呼吸危重症患者营养支持治疗实施过程中医务人员最为关注的22个问题进行了多轮讨论,经过专家投票计分最终确定24条推荐意见。本共识推荐意见根据循证医学证据,采用GRADE分级原则[1]对共识每条意见的推荐强度进行计分评价。综合推荐强度分0~ 9分共10个等级 ,0分为不推荐,9分为强力推荐,分数由低到高表示推荐强度逐渐增强。每条意见的推荐强度数值以均数±标准差(xˉ±s)格式表示。对于本共识中涉及的一些特殊名词,我们在此给予注解,以便于理解:

营养风险:因营养有关因素对患者临床结局(包括感染相关并发症、住院日等)发生不利影响的风险。

理想体重 (IBW):男性 :IBW(kg)=52+1.9 ×[身高 (cm)/2.54- 60];女性:IBW(kg)=49+1.7×[身高(cm)/2.54- 60]。

间接测热法(IC):通过代谢监测系统测定人体消耗的氧气量 、生成的二氧化碳量和排出的尿氮量并计算出人体所生成热能的方法。

过度喂养:实际能量摄入大于目标能量的110%。

低热量喂养:实际能量摄入低于目标能量的70%。

滋养型肠内营养:维持机体功能的最低喂养量,其目的是保护小肠上皮细胞、刺激十二指肠纹状缘分泌酶类、增强免疫功能、保护上皮细胞间的紧密连接以及防止菌群移位。通常定义为10~ 20 kcal/h或不超过500 kcal/d。

全肠外营养(TPN):全部营养要素从静脉途径供给。

补充型肠外营养(SPN):肠内营养 (EN)不足时 ,部分营养要素由静脉途径来补充的混合营养支持治疗方式。

呼吸商 (RQ):营养物质氧化过程中生成的二氧化碳与所消耗的氧气容积比值。

口服营养补充(ONS):当膳食提供的能量、蛋白质等营养素在目标需求量的50%~ 75%时,应用EN制剂或特殊医学用途配方食品进行口服补充的一种营养支持方法。

一、呼吸危重症患者如何进行营养风险筛查?

【推荐意见】

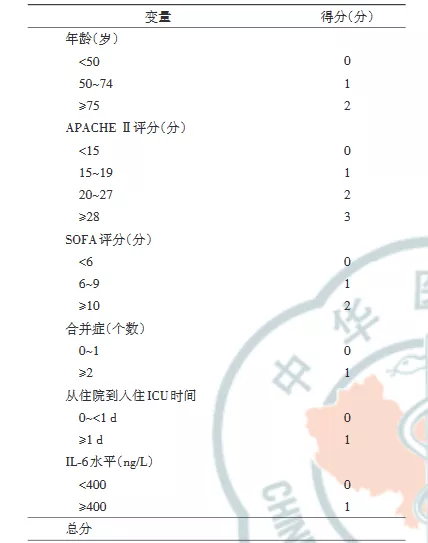

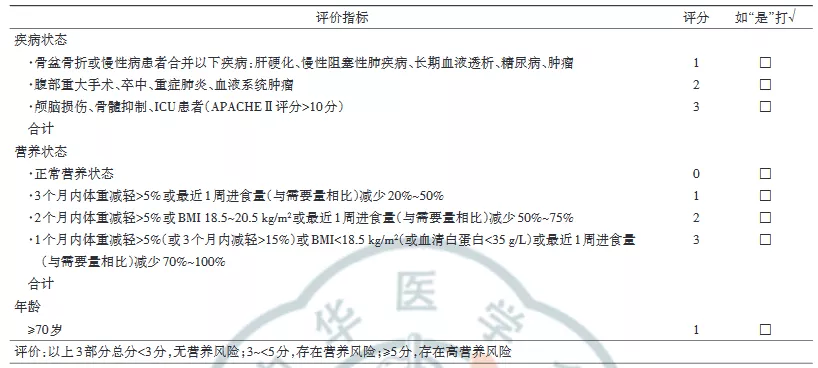

推荐对所有呼吸危重症患者应用危重症营养风险(NUTRIC)评分表 (表1)[2]或营养风险筛查2002(NRS‑2002)评分表 (表2)[3]进行营养风险筛查。NUTRIC评分≥6分[不考虑白细胞介素 (IL)‑6时≥5分]或者NRS‑2002评分≥5分的患者存在高营养风险,此类患者最有可能从早期营养支持治疗中获益。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.4± 0.9)分

说明:呼吸系统疾病的住院患者存在营养风险的比例为34.69%[4],而呼吸危重症患者更易合并营养不良或营养状态恶化进而导致不良预后,需要对此类患者进行识别并给予营养支持治疗。所有ICU住院患者,尤其是住院时间超过48 h者均应视为存在营养不良风险,应进行营养风险筛查[5]。目前有很多用于营养风险筛查的量表或工具[6],但只有NRS‑2002评分表与NUTRIC评分表同时纳入营养状态评分与疾病状态评分[2‑3]。NRS‑2002≥ 3分与内科急症住院患者30 d内病死率、再住院率显著正相关 ,与非住院时间呈负相关[7]。NUTRIC评分≥6分(不考虑IL‑6则应≥5分)与内科ICU患者28 d病死率具有独立正相关[8]。因此 ,NRS‑2002> 3分的患者被认为存在营养风险,NRS‑2002≥ 5分或NUTRIC评分≥6分(不考虑IL‑6则应≥5分)的患者被认为存在高营养风险[2‑3]。对于高营养风险的患者给予早期营养支持治疗可减少院内感染、减少并发症及降低病死率[8‑9]。与NRS‑2002评分相比,NUTRIC评分与蛋白质及能量供给不足的关系更为密切[10],提示使用NUTRIC评分对ICU患者进行营养风险筛查可能更有优势,但目前尚缺乏高质量的前瞻性研究对比NUTRIC评分和NRS‑2002评分在指导营养干预策略上的优劣性。

二、如何确定呼吸危重症患者的能量及蛋白质供给?

【推荐意见a】

建议使用基于体重估算能量消耗的简单公式[25~30 kcal·kg-1(实际体重)·d-1]来估算能量需求。如果有条件,建议使用IC法确定能量需求。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.1± 1.2)分

表1 NUTRIC评分表[2]

注:NUTRIC评分为危重症营养风险评分;APACHEII评分为急性生理及慢性健康状况评分;SOFA评分为序贯器官功能障碍评分;IL‑6为白细胞介素‑6;NUTRIC评分≥6分(不包含IL‑6则应≥5分)视为高营养风险

表2 营养风险筛查NRS‑2002评分表[3]

注:NRS‑2002评分为营养风险筛查2002评分;ICU为重症监护病房;APACHEII评分为急性生理及慢性健康状况评分;BMI为体质指数

说明:在开始营养支持治疗之前,应首先确定患者的能量需求,即目标喂养量。能量需求的计算可以根据以下方法:基于体重估算能量消耗的简单公式 [25~ 30 kcal·kg-1(实际体重 )·d-1]、其他已发表的预测公式或者IC法。IC法是目前最为准确的计算患者能量需求的方法[11‑12],但由于实用性及成本问题,在大多数医疗机构难以广泛开展。基于体重估算能量消耗的简单公式准确性较低,并受多种因素影响,如体重 、药物 、治疗情况、体温等 ,但公式简便实用便于开展。对于接受较大量的液体复苏或存在全身性水肿的患者,应根据患者平时的体重计算能量供给。对于肥胖的患者,应根据体质指数(BMI)调整能量需求:BMI 30~ 50 kg/m2时,按照11~ 14 kcal·kg-1(实际体重)·d-1计算 ;BMI>50 kg/m2时,按照22~ 25 kcal·kg-1(IBW)·d-1计算[13]。严重喂养不足或过度喂养均可能增加病死率、延长住院时间和机械通气时间[14‑15],应尽量避免。无论是通过IC法测量还是通过简单公式估算,能量消耗应每周至少重新评估一次,以优化能量和蛋白质摄入策略。

【推荐意见b】

建议以1.2~ 2.0 g·kg-1(实际体重 )·d-1估算蛋白质需求量。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.7 ±1.4)分

说明:与总能量供给相比,高蛋白质摄入与危重症患者临床结局改善的关系更为密切,蛋白质摄入≥1.2 g·kg-1(实际体重 )·d-1可降低ICU患者病死率 ,缩短住院时间[14,16]。因此 ,建议以1.2~ 2.0 g·kg-1(实际体重)·d-1估算呼吸危重症患者蛋白质需求 。对于BMI 30~ 40 kg/m2患者 ,按照2.0 g·kg-1(IBW)·d-1计算蛋白质需求;BMI≥40 kg/m2时,按照2.5 g·kg-1(IBW)·d-1计算[13]。对于急性肾损伤且接受血液透析或连续肾脏替代治疗的患者,最大剂量可达2.5 g·kg-1(实际体重)·d-1[17]。

三、早期EN是否能使呼吸危重症患者获益?血流动力学不稳定的呼吸危重症患者何时启动EN?

【推荐意见】

与延迟EN或不用EN比较 ,早期EN可以使呼吸危重症患者获益。对于血流动力学稳定的患者,建议尽早 (入ICU 24~ 48 h内)启动EN;对于血流动力学不稳定的患者,建议待血流动力学稳定后尽早开始EN,初始剂量为10~ 20 kcal/h,同时需警惕胃肠道并发症情况。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.3 ±1.1)分

说明:早期EN是指入院48 h以内启动EN,延迟EN是指入院48 h以后启动EN。多篇荟萃分析结果表明,与延迟EN或不用EN相比,早期EN可以显著降低病死率[18‑19]和感染发生率[13,18‑19],维护肠黏膜的屏障及免疫功能[20]。因此 ,无EN禁忌证并且血流动力学稳定患者,建议早期进行EN(入ICU 24~ 48 h内)[18‑19,21]。

对于需要低剂量血管活性药物(去甲肾上腺素当量<0.14 μg·kg-1·min-1)的机械通气脓毒症休克患者 ,早期EN(平均摄入剂量为16 kcal·kg-1·d-1)是可以耐受并安全的[22]。对于需要较大剂量血管活性药物 (去甲肾上腺素均值为0.50 /0.56 μg·kg-1·min-1)的机械通气患者,对比早期EN组(平均摄入热量17.8 kcal·kg-1·d-1)与肠外营养(PN)组(平均摄入热量19.6 kcal·kg-1·d-1),两组病死率、住院时间、机械通气时间及感染率无明显差异,但EN组相关的并发症如呕吐、腹泻等明显增加[23]。因此 ,对于血流动力学不稳定的患者,应延迟EN,待血流动力学稳定后开始低剂量(10~ 20 kcal/h)EN[13],同时需警惕胃肠道并发症情况。

四、启动EN之前是否需评估胃肠道功能?

【推荐意见】

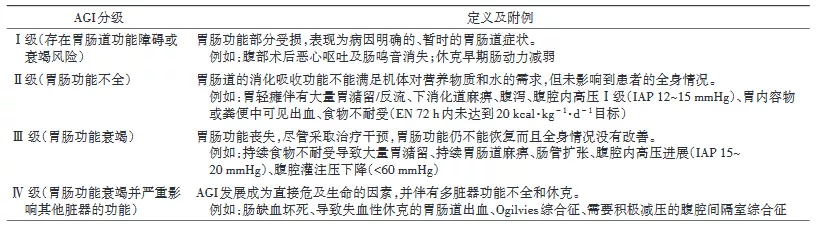

所有患者在实施EN前均应评估胃肠功能。推荐使用急性胃肠损伤(AGI)分级系统[24](表3)评估胃肠功能。建议AGI I~II级患者可考虑启动EN,AGI III级患者需谨慎地从小剂量EN开始尝试,AGI IV级患者需延迟EN的启动 。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.9± 1.4)分

表3 AGI分级表[24]

注:AGI为急性胃肠损伤;IAP为腹腔内压;EN为肠内营养;1 mmHg=0.133 kPa

说明:20%~85%危重症患者合并急性胃肠功能障碍[25‑27]。多项前瞻性研究及荟萃分析提示胃肠功能损伤严重程度与病死率呈正相关,是死亡风险增加的独立预测因素[25,27‑29]。因此 ,危重症患者启动EN前均应评估胃肠功能。临床常见的胃肠功能障碍包括胃肠动力障碍、消化吸收不良、黏膜屏障功能障碍及胃肠分泌功能障碍。目前尚缺乏一种理想的指标能够全面客观地评估胃肠功能。AGI分级系统能初步评估患者的消化吸收功能,与早期EN的成功实施存在较好的相关性,且对患者胃肠不耐受的发生及临床预后具有预测价值[27,29]。与无AGI和AGI I~II级患者相比,AGI III~IV级尤其是AGI IV级患者给予EN病死率显著增高[25,29‑30]。我们推荐AGI I~II级患者可考虑启动EN,AGI III级患者需谨慎地从小剂量EN开始尝试,AGI IV级患者需延迟EN的启动。

五、呼吸危重症患者如何选择EN配方?

【推荐意见】

首选标准整蛋白配方EN。存在胃肠不耐受患者,在排除其他EN不耐受原因后,可考虑使用短肽配方。需要限制容量的患者,建议采用高密度营养配方制剂。存在应激性高血糖的患者 ,建议采用糖尿病特异性配方。不建议常规应用富含纤维的配方制剂。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.9± 1.1)分

说明:标准整蛋白配方在大多数危重症患者中耐受良好且经济实惠,可以常规选择[13]。研究提示 ,与整蛋白配方组相比,短肽配方组危重症患者蛋白质摄入更多,胃肠道不良反应天数更少[31],ICU住院时间缩短并节省经济成本[32],但胃肠道不良事件发生次数无显著差异[33]。对于存在胃肠不耐受的呼吸危重症患者,在排除其他EN不耐受原因后, 可考虑使用短肽配方。

与等密度营养配方(1.0 kcal/ml)相比 ,高密度营养配方 (1.5 kcal/ml)可增加ICU患者每日热量摄入并降低90 d病死率 ,而两组胃肠不耐受及血糖升高无显著差异[34]。对需要限制容量的呼吸危重症患者, 建议采用高密度营养配方(1.3~ 1.5 kcal/ml)。

应激性高血糖增加患者感染风险及病死率[35‑36],在需要机械通气的急性呼吸衰竭患者发生率可高达89%[36]。与标准EN配方相比,糖尿病特异性配方可降低应激性高血糖重症患者血糖水平、减少胰岛素用量,并降低呼吸机相关性肺炎(VAP)和支气管炎发生率,但对机械通气时间、ICU住院时间及病死率均无改善[37‑38]。这2项研究中使用的糖尿病特异性配方均为低碳水化合物高脂肪酸[主要增加单个不饱和脂肪酸(MUFA)含量 ]配方 。因此,呼吸危重症患者出现应激性高血糖时,为稳定血糖 、减少胰岛素用量,可选用低碳水化合物高MUFA的糖尿病特异性配方。

荟萃分析结果显示,危重症患者腹泻率与应用富含纤维的EN制剂没有相关性[39]。因此 ,对富含纤维的配方不作常规推荐。

六、如何评估呼吸危重症患者EN的耐受性?

【推荐意见】

建议每日观察患者腹部张力、肠鸣音 、排便排气,以及有无呕吐、误吸等情况,必要时行腹部平片等检查,用于评估呼吸危重症患者的不耐受情况。出现明显腹胀时建议监测腹内压。胃残余量 (GRV)可不常规监测,出现不耐受表现时建议监测GRV。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.9± 1.0)分

说明:在尝试喂养后72 h内不能通过肠内途径达到20 kcal·kg-1·d-1的喂养量,或除治疗原因外其他原因导致EN的停止 ,则应认为存在喂养不耐受 (FI)[24]。FI可导致营养不良发生率、ICU住院天数 、非机械通气时间及病死率增加[40],临床应予以高度重视。EN不耐受的临床表现多样,腹痛 、腹胀 、恶心呕吐、腹泻 、肠鸣音亢进或减弱、误吸均提示可能存在FI,但目前尚无国际上公认FI程度的精确定义。

出现轻度FI表现可密切观察,继续EN。出现中度FI建议减慢EN输注速度,寻找原因给予对症处理 。以下情况应视为重度FI,需要暂停EN:误吸 、呕 吐 、GRV>500 ml[24]、腹 腔 内 压(IAP)>25 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)或出现腹腔间隔综合征[41]及AGI IV级[41]。受镇静 、机械通气等因素影响 ,呼吸危重症患者有时无法准确描述自己主观感受 ,应每日观察患者相关临床表现,出现明显腹胀建议监测腹内压及行腹部平片等检查[13,42]。

GRV测定受多种因素影响,不能有效反映FI情况 。有研究表明,与常规实行GRV监测相比,不实行GRV监测时小肠不耐受的发生率有明显降低。因此 ,不推荐GRV监测作为常规评估EN耐受性的指标[43],但出现腹胀、呕吐 、误吸等不耐受表现时建议监测GRV。

七、哪些呼吸危重症患者需要考虑存在误吸高风险?

【推荐意见】

既往有误吸史、意识水平降低(镇静 、颅内压升高)、神经肌肉疾病或呼吸消化道结构异常、呕吐 、机械通气或需要长时间水平仰卧、年龄>70岁、医护比不足、口腔护理不佳的呼吸危重症患者应考虑存在高误吸风险。不建议把GRV作为常规判断呼吸危重症误吸风险的指标。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.6± 1.4)分

说明:神经系统功能障碍或镇静过深造成的意识水平降低可导致食道下端括约肌功能受损、胃排空延迟以及咳嗽和咽反射减弱,增加误吸风险。长时间接受机械通气的患者由于插管时声门损伤 、气管切开对喉部运动的影响、喉顶骨肌长期不活动 、使用镇静及神经肌肉阻滞剂等原因可造成吞咽困难增加误吸风险[44]。机械通气患者水平仰卧位时较半卧位时的肺炎发生率显著增加[45]。老年人中枢神经系统活动减缓,吞咽能力随年龄的增长而下降,因此老龄患者应警惕误吸可能[46]。口腔中可能存在呼吸道致病菌定植,口腔护理不佳与吸入性肺炎患病率及病死率风险呈正相关[47]。GRV由50 ml增加到500 ml并不增加反流、误吸或者肺炎的发生率,故不推荐常规监测GRV[48‑49]。

八、如何提高呼吸危重症患者EN的耐受性和降低误吸风险?

【推荐意见】

推荐给予喂养时床头抬高30°~ 45°、加强口腔护理、幽门后喂养、促胃肠动力药物 、持续泵入EN而非间断喂养、减慢喂养速度、监测IAP及建立人工气道患者气管导管气囊充盈压不低于25 cmH2O(1 cmH2O=0.098 kPa)等措施以提高EN耐受性和降低误吸风险。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.1 ±1.1)分

说明:与仰卧位和低半靠位相比,将床头抬高30°~ 45°可以显著降低反流与误吸风险,减少医院获得性肺炎和VAP发生率[50]。每日给予氯己定溶液口腔护理可降低危重症患者误吸和VAP的发生率[51]。

与鼻胃管喂养相比,幽门后喂养能显著减少胃食道反流、误吸和吸入性肺炎的发生率[52]。存在误吸高风险的患者经静脉或胃肠使用胃肠动力药物,如红霉素或甲氧氯普胺等能显著减少GRV、改善胃排空能力及EN耐受性,降低误吸风险[53]。

与间断喂养相比,持续喂养耐受性更好、更快达到喂养目标而不明显增加其他不良事件[54],并且持续喂养患者ICU病死率更低[55]。因此 ,推荐对FI及误吸高风险患者实施持续喂养。接受EN的危重症患者出现FI及误吸的原因是多方面的,应先积极完善相关检查寻找原因,可尝试先减慢喂养速度, 除出现重度FI外, 不建议直接终止EN。

对不伴有腹腔间隔室综合征的IAP增高患者(IAP≥12 mmHg),早期EN并不增加IAP[56]。但不当的EN增加腹腔内容物可进一步增高IAP导致呕吐或误吸。建议至少每4 h监测1次IAP[57],若给予EN后IAP持续增高应减少(IAP 16~ 25 mmHg)或暂停(IAP>25 mmHg)EN。

气囊上滞留物是建立人工气道患者误吸的主要来源。研究表明持续监测气管导管气囊的充盈压可显著降低机械通气患者误吸风险,减少VAP的发生率[58]。因此建议保持气管导管气囊的充盈压不低于25 cmH2O。在气囊放气或拔出气管插管前应尽可能清除气囊上方及口腔内分泌物。

九、呼吸危重症患者如何给予PN?

【推荐意见a】

如EN不能实施,对于低营养风险患者,建议先短时间静脉输注葡萄糖支持,一周后若仍不能开放饮食则启动TPN;对于高营养风险患者 ,应在入ICU后尽早启动TPN,1周内先给予低热量TPN(≤20 kcal·kg-1·d-1或目标能量需求的80%和≥1.2 g·kg-1·d-1的蛋白质 ),再逐步过渡至足量PN。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.2± 1.7)分

说明:如果EN不可行时,需要启动PN。对于低营养风险患者,一周内给予TPN不能使患者获益,且延长机械通气时间及ICU住院时间,增加感染及死亡风险[59‑60]。与TPN相比 ,此时先使用短时间静脉输注葡萄糖支持治疗并尽早开放饮食的治疗策略 ,可以明显减少感染病死率[61‑62]。对于高营养风险患者,在EN不可行时,入院48 h内尽早启动TPN可降低感染及死亡风险[61‑62]。启动TPN的患者1周内低热量策略(≤20 kcal·kg-1·d-1或目标能量需求的80%和≥1.2 g·kg-1·d-1的蛋白质 )可降低感染发生率、机械通气时间[63]。

【推荐意见b】

呼吸危重症患者在给予7~ 10d的EN后,若EN仍不能满足60%的能量或蛋白质目标需求量,应该考虑给予SPN。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.6 ±1.3)分

说明:对于EN摄入不足的患者添加SPN的时机尚无一致观点。有研究表明,早于48 h补充PN,在临床结局上没有额外获益,并且增加经济负担[64]。对于机械通气患者,早于48 h补充PN,可以降低住院病死率、改善患者的生活质量[65]。近期一系列研究指出,在EN不足时 ,认为在入ICU后补充PN可以改善临床结局,但是开始的时间从第3到第10天不等 ,各项临床研究中SPN启动时间的差异主要是由于患者营养风险程度、病情严重程度、EN耐受情况、EN提供的能量或蛋白目标需求量的差异而造成的[62,66‑67]。目前仍建议给予7~ 10 d的EN仍不能满足机体的能量需求时,需要考虑给予SPN[65]。

十、急性呼吸窘迫综合征(ARDS)患者如何给予营养支持?

【推荐意见】

对于ARDS患者 ,推荐第一周内给予滋养型喂养(10~ 20 kcal / h或不超过500 kcal/d),后逐步过渡至足量喂养。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.9± 1.1)分

说明:针对ARDS/急性肺损伤(ALI)患者的2项RCT研究结果提示,前6 d滋养型喂养比足量喂养发生胃肠道不耐受率更低,且两组患者临床预后无差别[68]。与低热量喂养相比,接近目标热量喂养增加患者病死率[69]。但持续的能量负平衡会增加ICU患者的并发症,尤其是继发感染[70‑71]。因此,需在一定时间内达到能量供需平衡。最佳时机尚未明确,建议1周内给予滋养型喂养,1周后过渡至足量喂养。

十一、免疫调节配方是否推荐用于ARDS患者?

【推荐意见】

对于ARDS患者 ,我们不推荐常规使用含Omega‑3多不饱和脂肪酸(Ω‑3PUFA)、γ‑亚麻酸 (GLA)、琉璃苣油及抗氧化剂的免疫调节配方。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.1± 1.0)分

说明:Ω‑3 PUFA、GLA、琉璃苣油及抗氧化剂等免疫调节剂能为机体提供能量和必需脂肪酸,具有调节脂类合成、细胞因子释放、激活白细胞和内皮细胞活化等免疫调节作用,进而调控危重症患者机体内过度炎性反应。有研究结果提示给予二十碳五烯酸(EPA)+GLA,可缩短ARDS/ALI患者ICU住院时间及机械通气时间、减少新发器官衰竭,在氧合指标、肺顺应性以及机械通气时间均优于标准等氮等热卡EN配方组[72]。但也有研究结果提示添加特殊配方的EN制剂不能缩短ARDS患者机械通气的时间,也未能改善预后[73]。2项系统回顾和荟萃分析结果均认为现有证据不足以支持免疫调节配方在ARDS患者中的使用[74‑75]。

十二、俯卧位通气患者如何实施EN?

【推荐意见】

实施俯卧位通气的患者不应延误EN的启动 。有条件的优先考虑幽门后喂养,空肠管置入困难的应考虑鼻胃管喂养。建议床头抬高 (10°~ 25°)、给予胃肠动力药物并监测EN的耐受性。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.2± 1.6)分

说明:4项类似研究发现俯卧位患者可以很好地耐受EN,相对于仰卧位,俯卧位时以相同速度给予EN并未增加胃潴留、反流呕吐、VAP和住院病死率[76‑79]。一项研究发现相对于仰卧位通气患者,俯卧位通气的患者胃潴留更多,呕吐和终止EN的比例更高[80]。进一步的研究发现如果将俯卧位患者的上半身抬高25°并预防性给予胃肠动力药物(红霉素)则较仰卧位更高的喂养速度下可以改善EN的耐受性并增加EN的喂养量[77]。因此 ,可以谨慎尝试EN并使用胃肠动力药和改变体位以减少胃肠喂养的不耐受。临床为安全起见,可从低速喂养逐渐增加喂养速度。因俯卧位患者均使用较大剂量的镇静镇痛药物甚至肌松剂,且俯卧位可能会增加腹腔压力,因此俯卧位通气患者可优先考虑幽门后喂养。

十三、脓毒症患者如何实施EN?

【推荐意见】

无EN禁忌的脓毒症患者应早期启动EN(48 h内)。脓毒性休克患者,血流动力学稳定后尽早启动EN,由低热卡或滋养型喂养起始,一周达目标能量60%~ 70%,蛋白质1.2~ 2.0 g·kg-1·d-1。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.0± 1.2)分

说明:对于血流动力学稳定的脓毒症患者应早期 (48 h内)启动EN[81]。与无休克脓毒症患者相比 ,脓毒症休克患者GRV更高 ,但最终喂养达标率并无差异[82]。脓毒症休克患者存在血流动力学不稳定时,需根据血流动力学的状态决定启动EN的时机, 详见推荐意见3及说明。

脓毒症患者能量消耗个体差异大,IC法确定能量消耗最佳,如IC法不可行,则建议应用基于体重的计算公式[25~ 30 kcal·kg-1(实际体重 )·d-1]。脓毒性休克患者早期EN时,48 h内<600>600 kcal/d相比 ,喂养耐受性更好,ICU住院时间、机械通气时间更短且并不增加喂养相关并发症(误吸性肺炎、非梗阻性肠缺血、肠坏死 )的发生[83]。由于脓毒症患者急性期存在内源性供能 ,对于无EN禁忌脓毒症患者建议早期给予低热卡或滋养型喂养,24~ 48 h后逐渐加量,一周达到目标喂养量的60%~ 70%[84‑85]。

相对于单纯的足热量喂养,足热量高蛋白组(114.9 g/d)比低蛋白组(53.8 g/d)28 d病死率约下降50%[86]。建议按脓毒症患者1.2~ 2.0 g·kg-1·d-1估算目标蛋白质量[13],监测每日血尿素氮及24 h尿排氮量以调整蛋白质供给量。

十四、脓毒症患者能否从免疫调节配方中获益?

【推荐意见】

与标准配方相比,免疫调节配方不能使脓毒症患者额外获益。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.0 ±1.1)分

说明:免疫调节剂如EPA、Ω‑3 PUFA、GLA和抗氧化剂等,可调节多种促炎基因、细胞因子,从而调控危重症患者体内炎症反应和发挥抗氧化作用。早期的研究结果提示给予EPA+GLA和抗氧化剂,可减少脓毒症患者新发器官衰竭、减少气管插管率 、缩短ICU住院时间及总住院时间,但对氧合指数及感染并发症无明显改善[87‑89]。然而其后的研究提示富含EPA+GLA和抗氧化剂的EN不能减少脓毒症导致ARDS患者机械通气时间、SOFA评分、院内感染发生率及病死率,仅能缩短ICU住院时间[90]。两项荟萃分析结果提示,Ω‑3 PUFA可减少脓毒症和脓毒症诱导的ARDS患者的机械通气和ICU住院天数,但病死率无显著降低[91‑92]。

十五、是否推荐脓毒症患者常规补充益生菌?

【推荐意见】

目前证据尚不能对脓毒症患者常规使用益生菌做出推荐。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.3 ±1.6)分

说明:脓毒症会导致正常的肠道微生态受损造成肠道菌群失衡[93]。而益生菌可能通过竞争性抑制致病菌的生长、阻止致病菌对肠上皮的黏附和侵入 、增强肠屏障功能、调节宿主免疫反应等作用调节肠道微生态环境[94]。部分危重症患者应用益生菌可调节免疫功能、降低感染并发症和VAP的发生 、缩短ICU住院时间,但ICU病死率无明显获益[95‑96]。

十六、高脂低糖的营养配方是否适用于伴有高碳酸血症的慢阻肺急性加重患者?

【推荐意见】

高脂低糖的营养配方不推荐用于伴有高碳酸血症的慢阻肺急性加重患者。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.7± 1.1)分

说明:早期有学者发现部分接受高碳水化合物PN的患者出现了高碳酸血症及呼吸衰竭,原因是高糖营养会增大患者的呼吸商从而损伤呼吸功能 ,因此呼吸衰竭配方(高脂/低碳水化合物配方)应运而生[97]。有小样本研究曾认为这一配方可以缩短呼吸衰竭患者的机械通气时间[98]。但随后类似的大样本研究提示使用常规配方和呼吸衰竭配方的慢阻肺急性加重患者在ICU住院时间、机械通气时间和病死率方面并无显著差异[99]。与提高脂质含量相比,避免过度喂养更能减少营养相关高碳酸血症的发生[100]。营养配方中的糖脂比例也不是影响呼吸商的因素,且与患者预后无关,同时高脂配方还会明显延长胃排空的时间[101‑102]。

十七、 EN以及ONS能否使稳定期慢阻肺患者获益?

【推荐意见】

建议对稳定期慢阻肺患者给予EN以及ONS,能够通过改善营养状态和肌肉力量使其获益。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.7± 1.1)分

说明:在慢阻肺合并呼吸衰竭的住院患者中高达48%~ 83%的患者存在营养风险,而营养风险与患者的病死率存在正相关[103]。两篇荟萃分析的结果肯定了EN及ONS补充对稳定期的慢阻肺患者的作用,包括能量摄入、体重 、握力 、运动耐量、呼吸肌肉力量以及生活质量均有明显改善[104‑105]。

十八、补充维生素C/E/D能否使稳定期慢阻肺患者获益?

【推荐意见】

长期补充维生素C/E/D可以使稳定期慢阻肺患者获益。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.5 ±1.2)分

说明:慢阻肺患者肺部及全身氧化应激增强[106]。维生素C和E是人体内重要的非酶系抗氧化剂 ,可以降低全身氧化应激水平。大多数慢阻肺患者维生素C和E含量较低,在急性加重期下降更明显[107‑108]。较高水平的维生素C和E与第一秒用力呼气容积(FEV1)呈正相关[109],摄入较高剂量的维生素C可以延缓FEV1的下降速度[110]。增加维生素E的摄入量可能与中年男性慢阻肺患者20年死亡率下降存在相关性[111]。

慢阻肺患者普遍存在维生素D缺乏 ,导致从肠道钙吸收减少、损害骨骼钙化和继发性甲状旁腺功能亢进 ,从而导致骨质疏松和骨折风险增加[112],对慢阻肺患者生活质量及肺功能产生重要影响。维生素D缺乏也与慢阻肺患者病情严重程度、频繁急性加重相关[113]。补充维生素D可以改善慢阻肺患者FEV1水平[114],降低中度或重度急性加重风险[115],并使吸气肌力量、活动耐力、最大携氧量提高[116]。

十九、无创机械通气(NIV)患者选用何种营养支持方式?

【推荐意见】

实施NIV的患者 ,可经口进食且能够达到目标喂养量的70%以上者 ,建议首选经口进食 ,必要时给予ONS。对于存在呕吐和高GRV(>250 ml)等误吸高风险患者,建议给予胃肠动力药物或改为幽门后喂养。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.8± 1.4)分

说明:接受NIV的患者可能因会厌功能障碍或吞咽困难等原因导致气体进入消化道、IAP增加,存在呕吐及误吸风险。与未接受EN的患者相比,接受EN的NIV患者黏液栓形成和误吸发生率更高 、ICU住院时间更长,但病死率无显著差异[117]。与PN和口服营养相比,接受EN的NIV患者能量摄入减少 ,VAP、院内感染、插管率及病死率均显著增高[118]。因此 ,对于实施NIV的患者 ,可经口进食且能够达到目标喂养量的70%以上,建议首选经口进食,必要时给予ONS。有呕吐和高GRV(>250 ml)等误吸高风险的,建议常规给予胃肠动力药物[119]或改为幽门后喂养。间断应用经鼻高流量治疗代替NIV可能有助于增加患者营养摄入及减少相关并发症[120]。

二十、实施体外膜式氧合(ECMO)的患者是否可以早期应用EN?

【推荐意见】

无严重循环休克的ECMO患者可早期实施EN。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(8.1± 1.3)分

说明:近期一项回顾性研究提示喂养能量>80%目标量可改善ECMO患者病死率[121]。EN是呼吸重症患者建立VV‑ECMO后的主要营养支持方式[122‑123]。ECMO建立后48 h内(平均14 h)即可启动EN,但对于存在严重休克者,可适当延迟启动早期EN,并应在每日评估后选择合适的EN启动时机[122‑123]。可首选经鼻胃管喂养,如存在明显胃潴留应用胃肠动力药改善不佳或在有空肠置管经验的ICU,可首选经空肠管喂养[123]。ECMO患者每日能量和蛋白质供给应>70%~ 80%目标量[122‑123]。接受VV‑ECMO支持的患者 (尤其是肥胖患者)的蛋白质需求可能高于其他危重症患者,建议根据氮平衡计算蛋白质需求[124‑125]。

二十一、改善患者的营养状态能否增加肺移植患者存活率?

【推荐意见】

肺移植患者术前营养不足或肥胖都会导致术后病死率增加,改善患者的营养状态可增加患者的存活率。建议肺移植患者在术前术后将BMI调整至18.5~ 25.0 kg/m2之间 。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.5± 1.4)分

说明:肺移植患者的围术期营养不良并不少见,且与移植术前术后的生存率明显相关[126‑127]。营养不足 (低BMI、低白蛋白血症)和营养过剩(超重或肥胖 )都可能导致患者的预后变差,包括等待移植时的死亡风险与ICU/院内病死率会显著增加[128]。

建议术前BMI较低的营养不良受者积极增加能量和蛋白质摄入,经口摄入不足时可给予鼻饲或行胃造瘘术。而对于肥胖的肺移植受者建议其减重。术前通过肺康复和营养支持增加患者的肌肉重量 (增加合成代谢)是较为经济的改善预后的方法。

对于肺移植术后患者的营养相关研究甚少,建议进行全面的营养评估,给予患者充足的热量(25~30 kcal·kg-1·d-1)、蛋白质 (1.3~ 1.5 g·kg-1·d-1,急性应激期可能需要高达2.0~ 2.5 g·kg-1·d-1)、维生素和微量元素,使体重增加到正常范围,以保障患者伤口愈合、维持免疫功能、降低感染风险和协助康复锻炼[129]。

二十二、呼吸危重症患者喂养流程

【推荐意见】

荐呼吸危重症患者采用下列流程图进行营养支持治疗(图1)。

【推荐强度】

推荐强度:(7.9± 1.7)分

说明:推荐对呼吸危重症患者实施营养支持治疗进行标准化流程管理,其中主要包括:营养风险筛查、EN可行性筛查、误吸高风险筛查等决定营养支持给予途径,并根据疾病及患者耐受情况制定个体化的营养支持治疗目标计划,逐步达到目标喂养量并降低营养支持治疗的不良风险。

专家委员会成员(按姓氏汉语拼音排序):程真顺(武汉大学中南医院 );方保民(北京医院 );蒋进军(复旦大学附属中山医院 );胡国栋(南方医科大学南方医院);李丹(吉林大学第一医院 );李琦(陆军军医大学新桥医院);李彤(北京同仁医院);黎毅敏(广州医科大学附属第一医院);罗红(中南大学湘雅二医院 );宋立强(西京医院 );孙兵(北京朝阳医院);解立新(解放军总医院);邢丽华(郑州大学附属第一医院);詹庆元(中日友好医院);周庆涛(北京大学第三医院)

执笔者(按姓氏汉语拼音排序):陈淑靖(复旦大学附属中山医院 );杜毅鹏(北京大学第三医院);冯莹莹(中日友好医院);耿爽(华中科技大学同济医学院附属武汉中心医院 );贺航咏(北京朝阳医院);侯俊娜(郑州大学附属第一医院);胡国栋(南方医科大学南方医院);黄絮(中日友好医院);雷伟(苏州大学附属第一医院);李丹(北京同仁医院);梁瀛(北京大学第三医院);唐颖(吉林大学第一医院);王美菊(陆军军医大学新桥医院);韦超洁(武汉大学中南医院);谢菲(解放军总医院);徐建桥(解放军总医院);闫百灵(吉林大学第一医院);杨敏(中南大学湘雅二医院);张容(广州医科大学附属第一医院);钟雪锋(北京医院 );周长治(华中科技大学同济医学院附属武汉中心医院)

主要执笔者:耿爽、谢菲、黄絮、梁瀛

[1] Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al . GRADE: an emergingconsensus on rating quality of evidence and strength ofrecommendations[J]. BMJ, 2008, 336( 7650): 924‑926.DOI:10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD.

[2] Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, et al . Nutritional riskscreening(NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis ofcontrolled clinical trials[J]. Clin Nutr, 2003, 22( 3): 321‑336.DOI: 10.1016/s0261‑5614(02) 00214‑5.

[3] Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Jiang X , et al . Identifying criticallyill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: thedevelopment and initial validation of a novel risk assessmenttool[J]. Crit care, 2011, 15( 6): R268. DOI: 10.1186/cc10546.

[4] Maia I , Peleteiro B, Xará S , et al . Undernutrition Risk andUndernutrition in Pulmonology Department Inpatients: ASystematic Review and Meta‑Analysis[J]. J Am Coll Nutr,2017, 36( 2): 137‑147.DOI: 10.1080/07315724.2016.1209728.

[5] Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, et al . ESPEN guideline onclinical nutrition in the intensive care unit[J]. Clin Nutr, 2019,38( 1): 48‑79. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu .2018.08.037.

[6] Anthony PS. Nutrition screening tools for hospitalized patients[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2008, 23( 4): 373‑382.DOI: 10.1177/0884533608321130.

[7] Felder S, Lechtenboehmer C, Bally M, et al . Association ofnutritional risk and adverse medical outcomes across differentmedical inpatient populations[J]. Nutrition, 2015, 31( 11‑12):1385‑1393.DOI: 10.1016/j.nut .2015.06.007.

[8] Mukhopadhyay A, Henry J, Ong V , et al . Association ofmodified NUTRIC score with28‑day mortality in critically illpatients[J]. Clin Nutr, 2017, 36( 4): 1143‑1148.DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.08.004.

[9] Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Wang M, et al . The prevalence ofiatrogenic underfeeding in the nutritionally′at‑risk′ criticallyill patient: Results of an international, multicenter,prospective study[J]. Clin Nutr, 2015, 34( 4): 659‑666.DOI:10.1016/j.clnu .2014.07.008.

[10] Canales C, Elsayes A, Yeh DD, et al . Nutrition Risk inCritically Ill Versus the Nutritional Risk Screening2002: AreThey Comparable for Assessing Risk of Malnutrition inCritically Ill Patients?[ J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2019,43( 1): 81‑87. DOI: 10.1002/jpen.1181.

[11] Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl JL, et al . Assessment of restingenergy expenditure in mechanically ventilated patients[J]. AmJ Clin Nutr, 2003, 78( 2): 241‑249.DOI: 10.1093/ ajcn /78.2.241.

[12] Neelemaat F, Van Bokhorst‑De Van Der Schueren MA, ThijsA, et al . Resting energy expenditure in malnourished olderpatients at hospital admission and three months afterdischarge: predictive equations versus measurements[J]. ClinNutr, 2012, 31( 6): 958‑966.DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu .2012.04.010.

[13] Mcclave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al . Guidelines forthe Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy inthe Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical CareMedicine(SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral andEnteral Nutrition(A.S. P.E.N.)[ J]. JPEN J Parenter EnteralNutr, 2016,40( 2): 159‑211.DOI: 10.1177/0148607115621863.

[14] Compher C, Chittams J, Sammarco T, et al . Greater Proteinand Energy Intake May Be Associated With ImprovedMortality in Higher Risk Critically Ill Patients: A Multicenter,Multinational Observational Study[J]. Crit Care Med, 2017, 45(2): 156‑163.DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002083.

[15] Weijs PJ, Looijaard WG, Beishuizen A, et al . Early highprotein intake is associated with low mortality and energyoverfeeding with high mortality in non‑septic mechanicallyventilated critically ill patients[J]. Crit Care, 2014, 18( 6): 701.DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑014‑0701‑z.

[16] Nicolo M, Heyland DK, Chittams J, et al . Clinical OutcomesRelated to Protein Delivery in a Critically Ill Population: AMulticenter, Multinational Observation Study[J]. JPEN JParenter Enteral Nutr, 2016, 40( 1): 45‑51.DOI: 10.1177/0148607115583675.

[17] Scheinkestel CD, Kar L , Marshall K, et al . Prospectiverandomized trial to assess caloric and protein needs ofcriticallyIII, anuric, ventilated patients requiring continuousrenal replacement therapy[J]. Nutrition, 2003, 19( 11‑12):909‑916.DOI: 10.1016/s0899‑9007(03) 00175‑8.

[18] Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Early enteral nutrition in acutely illpatients: a systematic review[J]. Crit Care Med, 2001, 29( 12):2264‑2270.DOI: 10.1097/00003246‑200112000‑00005.

[19] Doig GS, Heighes PT, Simpson F, et al . Early enteralnutrition, provided within24 h of injury or intensive care unitadmission, significantly reduces mortality in critically illpatients: a meta‑analysis of randomised controlled trials[J].Intensive Care Med, 2009, 35( 12): 2018‑2027.DOI: 10.1007/s00134‑009‑1664‑4.

[20] Schorghuber M, Fruhwald S. Effects of enteral nutrition ongastrointestinal function in patients who are critically ill[J].Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 3( 4): 281‑287.DOI:10.1016/s2468‑1253(18) 30036‑0.

[21] Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, et al . Canadian clinica

ventilated, critically ill adult patients[J]. JPEN J ParenterEnteral Nutr, 2003,27( 5): 355‑373.DOI: 10.1177/0148607103027005355.

[22] Merchan C, Altshuler D, Aberle C, et al . Tolerability ofEnteral Nutrition in Mechanically Ventilated Patients WithSeptic Shock Who Require Vasopressors[J]. J Intensive CareMed, 2017, 32( 9): 540‑546.DOI: 10.1177/0885066616656799.

[23] Reignier J, Boisrame‑Helms J, Brisard L, et al . Enteral versusparenteral early nutrition in ventilated adults with shock: arandomised, controlled, multicentre, open‑label,parallel‑group study(NUTRIREA‑2) [ J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10116): 133‑143.DOI: 10.1016/s0140‑6736(17) 32146‑3.

[24] Reintam Blaser A, Malbrain ML, Starkopf J, et al .Gastrointestinal function in intensive care patients:terminology, definitions and management. Recommendationsof the ESICM Working Group on Abdominal Problems[J].Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38( 3): 384‑394.DOI: 10.1007/s00134‑011‑2459‑y.

[25] Zhang D, Li Y , Ding L , et al . Prevalence and outcome of acutegastrointestinal injury in critically ill patients: A systematicreview and meta‑analysis[J]. Medicine(Baltimore), 2018, 97(43): e12970. DOI: 10.1097/md.0000000000012970.

[26] Nguyen T, Frenette AJ, Johanson C, et al . Impairedgastrointestinal transit and its associated morbidity in theintensive care unit[J]. J Crit Care, 2013, 28( 4): 537. e11‑e 17.DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrc .2012.12.003.

[27] Hu B , Sun R , Wu A , et al . Severity of acute gastrointestinalinjury grade is a predictor of all‑cause mortality in critically illpatients: a multicenter, prospective, observational study[J].Crit Care, 2017, 21( 1): 188. DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑017‑1780‑4.

[28] Piton G, Belon F, Cypriani B, et al . Enterocyte damage incritically ill patients is associated with shock condition and28‑day mortality[J]. Crit Care Med, 2013, 41( 9): 2169‑2176.DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828c 26b5.

[29] Li H , Zhang D, Wang Y, et al . Association between acutegastrointestinal injury grading system and disease severity andprognosis in critically ill patients: A multicenter, prospective,observational study in China[J]. J Crit Care, 2016, 36: 24‑28.DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrc .2016.05.001.

[30] Xing J , Zhang Z, Ke L , et al . Enteral nutrition feeding inChinese intensive care units: a cross‑sectional study involving116 hospitals[J]. Crit Care, 2018, 22( 1): 229. DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑018‑2159‑x.

[31] Seres DS, Ippolito PR. Pilot study evaluating the efficacy,tolerance and safety of a peptide‑based enteral formula versusa high protein enteral formula in multiple ICU settings(medical, surgical, cardiothoracic)[ J]. Clin Nutr, 2017, 36( 3):706‑709.DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu .2016.04.016.

[32] Curry AS, Chadda S, Danel A, et al . Early introduction of asemi‑elemental formula may be cost saving compared to apolymeric formula among critically ill patients requiringenteral nutrition: a cohort cost‑consequence model[J].Clinicoecon Outcomes Res, 2018, 10: 293‑300.DOI: 10.2147/ceor.S155312.

[33] Jakob SM, Butikofer L, Berger D, et al . A randomizedcontrolled pilot study to evaluate the effect of an enteralformulation designed to improve gastrointestinal tolerance inthe critically ill patient‑the SPIRIT trial[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21(1): 140. DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑017‑1730‑1.

[34] Peake SL, Davies AR, Deane AM, et al . Use of a concentrated

enteral nutrition solution to increase calorie delivery tocritically ill patients: a randomized, double‑blind, clinical trial[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2014, 100( 2): 616‑625.DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.114.086322.

[35] Falciglia M, Freyberg RW, Almenoff PL, et al .Hyperglycemia‑related mortality in critically ill patients varieswith admission diagnosis[J]. Crit Care Med, 2009, 37( 12):3001‑3009.DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b083f7.

[36] Edriss H, Selvan K, Sigler M, et al . Glucose Levels in PatientsWith Acute Respiratory Failure Requiring MechanicalVentilation[J]. J Intensive Care Med, 2017, 32( 10): 578‑584.DOI: 10.1177/0885066616636013.

[37] Mesejo A, Montejo‑Gonzalez JC, Vaquerizo‑Alonso C, et al .Diabetes‑specific enteral nutrition formula in hyperglycemic,mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a prospective,open‑label, blind‑randomized, multicenter study[J]. Crit Care,2015,19:390.DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑015‑1108‑1.

[38] Van Steen SC, Rijkenberg S, Sechterberger MK, et al .Glycemic Effects of a Low‑Carbohydrate Enteral FormulaCompared With an Enteral Formula of Standard Compositionin Critically Ill Patients: An Open‑Label RandomizedControlled Clinical Trial[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr,2018, 42( 6): 1035‑1045.DOI: 10.1002/jpen.1045.

[39] Kamarul Zaman M,Chin KF, Rai V , et al . Fiber and prebioticsupplementation in enteral nutrition: A systematic review andmeta‑analysis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015,21( 17):5372‑5381.DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v 21.i 17.5372.

[40] Gungabissoon U, Hacquoil K, Bains C, et al . Prevalence, riskfactors, clinical consequences, and treatment of enteral feedintolerance during critical illness[J]. JPEN J Parenter EnteralNutr, 2015,39( 4): 441‑448.DOI: 10.1177/0148607114526450.

[41] Reintam Blaser A, Starkopf J, Alhazzani W, et al . Earlyenteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinicalpractice guidelines[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2017, 43( 3):380‑398.DOI: 10.1007/s00134‑016‑4665‑0.

[42] Woodcock NP, Zeigler D, Palmer MD, et al . Enteral versusparenteral nutrition: a pragmatic study[J]. Nutrition, 2001, 17(1): 1‑12.DOI:10.1016/s0899‑9007(00) 00576‑1.

[43] Poulard F, Dimet J, Martin‑Lefevre L, et al . Impact of notmeasuring residual gastric volume in mechanically ventilatedpatients receiving early enteral feeding: a prospectivebefore‑after study[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2010, 34(2): 125‑130.DOI: 10.1177/0148607109344745.

[44] Tolep K, Getch CL, Criner GJ. Swallowing dysfunction inpatients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation[J]. Chest,1996, 109( 1): 167‑172.DOI: 10.1378/chest.109.1.167.

[45] Drakulovic MB, Torres A, Bauer TT, et al . Supine bodyposition as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia inmechanically ventilated patients: a randomised trial[J].Lancet, 1999,354( 9193):1851‑1858.DOI: 10.1016/S0140‑6736(98) 12251‑1.

[46] Elpern EH. Pulmonary aspiration in hospitalized adults[J].Nutr Clin Pract, 1997,12( 1): 5‑13. DOI: 10.1177/011542659701200105.

[47] Bassim CW, Gibson G, Ward T , et al . Modification of the riskof mortality from pneumonia with oral hygiene care[J]. J AmGeriatr Soc, 2008,56( 9): 1601‑1607.DOI: 10.1111/j.1532‑5415.2008.01825.x.

[48] Pinilla JC, Samphire J, Arnold C, et al . Comparison ofgastrointestinal tolerance to two enteral feeding protocols in critically ill patients: a prospective, randomized controlled trial[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2001, 25( 2): 81‑86. DOI:10.1177/014860710102500281.

[49] Montejo JC, Minambres E, Bordeje L, et al . Gastric residualvolume during enteral nutrition in ICU patients: the REGANEstudy[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2010, 36( 8): 1386‑1393.DOI:10.1007/s00134‑010‑1856‑y.

[50] Van Nieuwenhoven CA, Vandenbroucke‑Grauls C, Van TielFH, et al . Feasibility and effects of the semirecumbentposition to prevent ventilator‑associated pneumonia: arandomized study[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34( 2): 396‑402.DOI: 10.1097/01.ccm .0000198529.76602.5e.

[51] Klompas M, Speck K, Howell MD, et al . Reappraisal ofroutine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patientsreceiving mechanical ventilation: systematic review andmeta‑analysis[J]. JAMA Intern Med, 2014, 174( 5): 751‑761.DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.359.

[52] Montejo JC, Grau T , Acosta J, et al . Multicenter, prospective,randomized, single‑blind study comparing the efficacy andgastrointestinal complications of early jejunal feeding withearly gastric feeding in critically ill patients[J]. Crit Care Med,2002, 30( 4): 796‑800.DOI: 10.1097/00003246‑200204000‑00013.

[53] Lewis K, Alqahtani Z, Mcintyre L, et al . The efficacy andsafety of prokinetic agents in critically ill patients receivingenteral nutrition: a systematic review and meta‑analysis ofrandomized trials[J]. Crit Care, 2016, 20( 1): 259. DOI:10.1186/s13054‑016‑1441‑z.

[54] Tavares De Araujo VM, Gomes PC, Caporossi C. Enteralnutrition in critical patients; should the administration becontinuous or intermittent? [ J]. Nutr Hosp, 2014, 29( 3):563‑567.DOI: 10.3305/nh.2014.29.3.7169.

[55] Macleod JB, Lefton J, Houghton D, et al . Prospectiverandomized control trial of intermittent versus continuousgastric feeds for critically ill trauma patients[J]. J Trauma,2007, 63( 1): 57‑61. DOI: 10.1097/01.ta .0000249294.58703.11.

[56] Sun JK , Li WQ , Ke L , et al . Early enteral nutrition preventsintra‑abdominal hypertension and reduces the severity ofsevere acute pancreatitis compared with delayed enteralnutrition: a prospective pilot study[J]. World J Surg, 2013, 37(9): 2053‑2060.DOI: 10.1007/s00268‑013‑2087‑5.

[57] Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J, et al .Intra‑abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartmentsyndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practiceguidelines from the World Society of the AbdominalCompartment Syndrome[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2013, 39( 7):1190‑1206.DOI: 10.1007/s00134‑013‑2906‑z.

[58] Nseir S, Lorente L, Ferrer M, et al . Continuous control oftracheal cuff pressure for VAP prevention: a collaborativemeta‑analysis of individual participant data[J]. Ann IntensiveCare, 2015, 5( 1): 43. DOI: 10.1186/s13613‑015‑0087‑3.

[59] Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, et al . Early versus lateparenteral nutrition in critically ill adults[J]. N Engl J Med,2011, 365( 6): 506‑517.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102662.

[60] Fivez T, Kerklaan D, Mesotten D, et al . Early versus LateParenteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Children[J]. N Engl JMed, 2016,374( 12): 1111‑1122.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514762.

[61] Doig GS, Simpson F, Sweetman EA, et al . Early parenteralnutrition in critically ill patients with short‑term relativecontraindications to early enteral nutrition: a randomized controlled trial[J]. JAMA, 2013, 309( 20): 2130‑2138.DOI:10.1001/jama.2013.5124.

[62] Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, et al . ESPEN guideline:Clinical nutrition in surgery[J]. Clin Nutr, 2017, 36( 3):623‑650.DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu .2017.02.013.

[63] Jiang H, Sun MW, Hefright B, et al . Efficacy of hypocaloricparenteral nutrition for surgical patients: a systematic reviewand meta‑analysis[J]. Clin Nutr, 2011, 30( 6): 730‑737.DOI:10.1016/j.clnu .2011.05.006.

[64] Kutsogiannis J, Alberda C, Gramlich L, et al . Early use ofsupplemental parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients:results of an international multicenter observational study[J].Crit Care Med, 2011, 39( 12): 2691‑2699.DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182282a83.

[65] Wischmeyer PE, Hasselmann M, Kummerlen C, et al . Arandomized trial of supplemental parenteral nutrition inunderweight and overweight critically ill patients: the TOP‑UPpilot trial[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21( 1): 142. DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑017‑1736‑8.

[66] Berger MM, Pichard C. Development and current use ofparenteral nutrition in critical care‑an opinion paper[J]. CritCare, 2014, 18( 4): 478. DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑014‑0478‑0.

[67] Heidegger CP, Berger MM, Graf S , et al . Optimisation ofenergy provision with supplemental parenteral nutrition incritically ill patients: a randomised controlled clinical trial[J].Lancet, 2013, 381( 9864): 385‑393.DOI: 10.1016/S 0140‑6736(12) 61351‑8.

[68] Rice TW, Susan M, Hays MA, et al . Randomized trial of initialtrophic versus full‑energy enteral nutrition in mechanicallyventilated patients with acute respiratory failure[J]. Crit Care Med,2011 ,39 (5):967 .DOI :10 .1097 /CCM .则0b013 e31820 a905 a.

[69] Braunschweig CA, Sheean PM, Peterson SJ, et al . Intensivenutrition in acute lung injury: a clinical trial(INTACT)[ J].JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2015, 39( 1): 13‑20.DOI:10.1177/0148607114528541.

[70] Dvir D , Cohen J, Singer P. Computerized energy balance andcomplications in critically ill patients: an observational study[J]. Clin Nutr, 2006, 25( 1): 37‑44.DOI: 10.1016/ j .clnu.2005.10.010.

[71] Villet S , Chiolero RL, Bollmann MD, et al . Negative impact ofhypocaloric feeding and energy balance on clinical outcome inICU patients[J]. Clin Nutr, 2005, 24( 4): 502‑509.DOI:10.1016/j.clnu .2005.03.006.

[72] Gadek JE, Demichele SJ, Karlstad MD, et al . Effect of enteralfeeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma‑linolenic acid, andantioxidants in patients with acute respiratory distresssyndrome. Enteral Nutrition in ARDS Study Group[J]. CritCare Med, 1999,27( 8): 1409‑1420.DOI: 10.1097/00003246‑199908000‑00001.

[73] Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, et al . Enteral omega‑3fatty acid, gamma‑linolenic acid, and antioxidantsupplementation in acute lung injury[J]. JAMA, 2011, 306( 14):1574‑1581.DOI: 10.1001/jama.2011.1435.

[74] Zhu D , Zhang Y, Li S , et al . Enteral omega‑3 fatty acidsupplementation in adult patients with acute respiratorydistress syndrome: a systematic review of randomizedcontrolled trials with meta‑analysis and trial sequentialanalysis[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2014, 40( 4): 504‑512.DOI:10.1007/s00134‑014‑3244‑5.

[75] Santacruz CA, Orbegozo D, Vincent JL, et al . Modulation ofDietary Lipid Composition During Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta‑Analysis[J]. JPEN JParenter Enteral Nutr, 2015, 39( 7): 837‑846.DOI: 10.1177/0148607114562913.

[76] Van Der Voort PH, Zandstra DF. Enteral feeding in thecritically ill: comparison between the supine and pronepositions: a prospective crossover study in mechanicallyventilated patients[J]. Crit Care, 2001, 5( 4): 216‑220.DOI:10.1186/cc1026.

[77] Reignier J, Dimet J , Martin‑Lefevre L, et al . Before‑after studyof a standardized ICU protocol for early enteral feeding inpatients turned in the prone position[J]. Clin Nutr, 2010, 29( 2):210‑216.DOI:10.1016/j.clnu .2009.08.004.

[78] Saez De La Fuente I, Saez De La Fuente J, Quintana EstellesMD, et al . Enteral Nutrition in Patients Receiving MechanicalVentilation in a Prone Position[J]. JPEN J Parenter EnteralNutr, 2016,40( 2): 250‑255.DOI: 10.1177/0148607114553232.

[79] Lucchini A, Bonetti I, Borrelli G, et al . Enteral nutritionduring prone positioning in mechanically ventilated patients[J]. Assist Inferm Ric, 2017, 36( 2): 76‑83.DOI: 10.1702/2721.27752.

[80] Reignier J, Thenoz‑Jost N, Fiancette M, et al . Early enteralnutrition in mechanically ventilated patients in the proneposition[J]. Crit Care Med, 2004, 32( 1): 94‑99. DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104208.23542.A8.

[81] Yang S , Wu X , Yu W , et al . Early enteral nutrition in criticallyill patients with hemodynamic instability: an evidence‑basedreview and practical advice[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2014, 29( 1):90‑96. DOI: 10.1177/0884533613516167.

[82] Rai SS , O′connor SN, Lange K, et al . Enteral nutrition forpatients in septic shock: a retrospective cohort study[J]. CritCare Resusc, 2010, 12( 3): 177‑181.

[83] Patel JJ, Kozeniecki M, Biesboer A, et al . Early TrophicEnteral Nutrition Is Associated With Improved Outcomes inMechanically Ventilated Patients With Septic Shock: ARetrospective Review[J]. J Intensive Care Med, 31( 7):471‑477.DOI: 0885066614554887.

[84] Levy MM, Artigas A, Phillips GS, et al . Outcomes of theSurviving Sepsis Campaign in intensive care units in the USAand Europe: a prospective cohort study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis,12( 12): 919‑924.DOI: 10.1016/S1473‑3099(12) 70239‑6.

[85] Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al . Surviving sepsiscampaign: international guidelines for management of severesepsis and septic shock: 2012[J]. Crit Care Med, 2013, 41( 2):580‑637.DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e 83af .

[86] Allingstrup MJ, Esmailzadeh N, Wilkens Knudsen A, et al .Provision of protein and energy in relation to measuredrequirements in intensive care patients[J]. Clin Nutr, 2012, 31(4): 462‑468.DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu .2011.12.006.

[87] Pontes‑Arruda A, Martins LF, De Lima SM, et al . Enteralnutrition with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma‑linolenic acidand antioxidants in the early treatment of sepsis: results from amulticenter, prospective, randomized, double‑blinded,controlled study: the INTERSEPT study[J]. Crit Care, 2011, 15(3): R144. DOI: 10.1186/cc10267.

[88] Pontes‑Arruda A, Aragao AM, Albuquerque JD. Effects ofenteral feeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma‑linolenicacid, and antioxidants in mechanically ventilated patients withsevere sepsis and septic shock[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34( 9):2325‑2333.DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000234033.65657.B6.

[89] Grau‑Carmona T, Moran‑Garcia V, Garcia‑De‑Lorenzo A, et al Effect of an enteral diet enriched with eicosapentaenoic acid,gamma‑linolenic acid and anti‑oxidants on the outcome ofmechanically ventilated, critically ill, septic patients[J]. ClinNutr, 2011, 30( 5): 578‑584.DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu .2011.03.004.

[90] Shirai K, Yoshida S, Matsumaru N, et al . Effect of enteral dietenriched with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma‑linolenic acid,and antioxidants in patients with sepsis‑induced acuterespiratory distress syndrome[J]. J Intensive Care, 2015, 3( 1):24. DOI: 10.1186/s40560‑015‑0087‑2.

[91] Lu C , Sharma S, Mcintyre L, et al . Omega‑3 supplementationin patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta‑analysisof randomized trials[J]. Ann Intensive Care, 2017, 7( 1): 58.DOI: 10.1186/s13613‑017‑0282‑5.

[92] Chen H, Wang S, Zhao Y, et al . Correlation analysis ofomega‑3 fatty acids and mortality of sepsis and sepsis‑inducedARDS in adults: data from previous randomized controlledtrials[J]. Nutr J, 2018,17( 1): 57. DOI: 10.1186/s12937‑018‑0356‑8.

[93] Cabrera‑Perez J, Badovinac VP, Griffith TS. Entericimmunity, the gut microbiome, and sepsis: Rethinking thegerm theory of disease[J]. Exp Biol Med(Maywood), 2017, 242(2): 127‑139.DOI:10.1177/1535370216669610.

[94] Sanders ME, Merenstein DJ, Reid G , et al . Probiotics andprebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to theclinic[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, Oct;16( 10):605‑616.DOI: 10.1038/s41575‑019‑0173‑3.

[95] Alberda C, Gramlich L, Meddings J, et al . Effects of probiotictherapy in critically ill patients: a randomized, double‑blind,placebo‑controlled trial[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007, 85( 3):816‑823.DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.816.

[96] Zeng J , Wang CT, Zhang FS, et al . Effect of probiotics on theincidence of ventilator‑associated pneumonia in critically illpatients: a randomized controlled multicenter trial[J].Intensive Care Med, 2016, 42( 6): 1018‑1028.DOI: 10.1007/s00134‑016‑4303‑x.

[97] Malone AM. Specialized enteral formulas in acute and chronicpulmonary disease[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2009, 24( 6): 666‑674.DOI: 10.1177/0884533609351533.

[98] Al‑Saady NM, Blackmore CM, Bennett ED. High fat, lowcarbohydrate, enteral feeding lowers PaCO2 and reduces theperiod of ventilation in artificially ventilated patients[J].Intensive Care Med, 1989, 15( 5): 290‑295.DOI: 10.1007/bf00263863.

[99] Mesejo A, Acosta JA, Ortega C, et al . Comparison of ahigh‑protein disease‑specific enteral formula with ahigh‑protein enteral formula in hyperglycemic critically illpatients[J]. Clin Nutr, 2003, 22( 3): 295‑305.DOI: 10.1016/s0261‑5614(02) 00234‑0.

[100]Talpers SS, Romberger DJ, Bunce SB, et al . Nutritionallyassociated increased carbon dioxide production. Excess totalcalories vs high proportion of carbohydrate calories[J]. Chest,1992, 102( 2): 551‑555.DOI: 10.1378/chest.102.2.551.

[101]Akrabawi SS, Mobarhan S, Stoltz RR, et al . Gastric emptying,pulmonary function, gas exchange, and respiratory quotientafter feeding a moderate versus high fat enteral formula mealin chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients[J].Nutrition, 1996, 12( 4): 260‑265.DOI: 10.1016/s 0899‑9007(96)90853‑9.

[102]Al‑Dorzi HM, Aldawood AS, Tamim H, et al . Caloric intakeand the fat‑to‑carbohydrate ratio in hypercapnic acuterespiratory failure: Post‑hoc analysis of the PermiT trial[J].··584 Clin Nutr ESPEN, 2019, 29: 175‑182.DOI: 10.1016/ j .clnesp.2018.10.012.

[103]Chen R, Xing L, You C. Nutritional risk screening2002 should be used in hospitalized patients with chronicobstructive pulmonary disease with respiratory failure todetermine prognosis: A validation on a large Chinese cohort[J].Eur J Intern Med, 2016, 36: e16‑e 17. DOI: 10.1016/ j .ejim.2016.08.014.

[104]Collins PF, Stratton RJ, Elia M . Nutritional support in chronicobstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review andmeta‑analysis[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2012, 95( 6): 1385‑1395.DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.111.023499.

[105]Ferreira IM, Brooks D, White J, et al . Nutritionalsupplementation for stable chronic obstructive pulmonarydisease[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012, 12: Cd000998.DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000998.pub3.

[106]Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Bracke KR. New insights into theimmunology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J].Lancet, 2011,378( 9795):1015‑1026.DOI: 10.1016/s0140‑6736(11) 60988‑4.

[107]Tug T , Karatas F, Terzi SM. Antioxidant vitamins(A, C and E)and malondialdehyde levels in acute exacerbation and stableperiods of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Clin Invest Med, 2004, 27( 3): 123‑128.

[108]Rodriguez‑Rodriguez E, Ortega RM, Andres P, et al .Antioxidant status in a group of institutionalised elderlypeople with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[J]. Br JNutr, 2016,115( 10): 1740‑1747.DOI: 10.1017/S0007114516000878.

[109]Butland BK, Fehily AM, Elwood PC. Diet, lung function, andlung function decline in a cohort of2512 middle aged men[J].Thorax, 2000, 55( 2): 102‑108.DOI: 10.1136/thorax.55.2.102.

[110]Mckeever TM, Scrivener S, Broadfield E, et al . Prospectivestudy of diet and decline in lung function in a generalpopulation[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2002, 165( 9):1299‑1303.DOI: 10.1164/rccm.2109030.

[111]Walda IC, Tabak C, Smit HA, et al . Diet and20‑year chronicobstructive pulmonary disease mortality in middle‑aged menfrom three European countries[J]. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2002, 56( 7):638‑643.DOI: 10.1038/sj.ejcn .1601370.

[112]Holick M. Vitamin D deficiency[J]. N Engl J Med, 2007, 357(3): 266‑281.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra070553.

[113]Malinovschi A, Masoero M, Bellocchia M, et al . Severevitamin D deficiency is associated with frequent exacerbationsand hospitalization in COPD patients[J]. Respir Res, 2014, 15:131. DOI: 10.1186/s12931‑014‑0131‑0.

[114]Sluyter JD, Camargo CA, Waayer D, et al . Effect of Monthly,High‑Dose, Long‑Term Vitamin D on Lung Function: ARandomized Controlled Trial[J]. Nutrients, 2017, 9( 12) pii:E1353. DOI: 10.3390/nu9121353.

[115]Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, Hooper RL, et al . Vitamin D toprevent exacerbations of COPD: systematic review andmeta‑analysis of individual participant data from randomisedcontrolled trials[J]. Thorax, 2019, 74( 4): 337‑345.DOI:10.1136/thoraxjnl‑2018‑212092.

[116]Hornikx M, Van Remoortel H, Lehouck A, et al . Vitamin Dsupplementation during rehabilitation in COPD: a secondaryanalysis of a randomized trial[J]. Respir Res, 2012, 13: 84.DOI: 10.1186/1465‑9921‑13‑84.

[117]Kogo M, Nagata K, Morimoto T, et al . Enteral Nutrition Is Risk Factor for Airway Complications in Subjects UndergoingNoninvasive Ventilation for Acute Respiratory Failure[J].Respiratory Care, 2017, 62( 4): 459‑467.DOI: 10.4187/respcare.05003.

[118]Terzi N, Darmon M, Reignier J, et al . Initial nutritionalmanagement during noninvasive ventilation and outcomes: aretrospective cohort study[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21( 1): 293. DOI:10.1186/s13054‑017‑1867‑y.

[119]Kogo M , Nagata K, Morimoto T, et al . Enteral Nutrition DuringNoninvasive Ventilation: We Should Go Deeper in theInvestigation‑Reply[J]. Respir Care, 2017, 62( 8): 1119‑1120.DOI: 10.4187/respcare.05684.

[120]Singer P, Rattanachaiwong S. To eat or to breathe? The answeris both ! Nutritional management during noninvasive ventilation[J]. Crit Care, 2018,22( 1): 27. DOI: 10.1186/s13054‑018‑1947‑7.

[121]Lu MC, Yang MD, Li PC , et al . Effects of NutritionalIntervention on the Survival of Patients with CardiopulmonaryFailure Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane OxygenationTherapy[J]. In Vivo, 2018, 32( 4): 829‑834.DOI: 10.21873/invivo.11315.

[122]Ferrie S, Herkes R, Forrest P. Nutrition support duringextracorporeal membrane oxygenation(ECMO) in adults:aretrospective audit of86 patients[J]. Intensive Care Med,2013, 39( 11): 1989‑1994.DOI: 10.1007/s00134‑013‑3053‑2

[123]Macgowan L, Smith E, Elliott‑Hammond C, et al . Adequacy ofnutrition support during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[J]. Clin Nutr, 2019, 38( 1): 324‑331.DOI: 10.1016/ j .clnu.2018.01.012.

[124]Pelekhaty SL, Galvagno SM Jr, Lantry JH, et al . Are CurrentProtein Recommendations for the Critically Ill Adequate forPatients on VV ECMO: Experience From a High‑VolumeCenter[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2019, May 15. DOI:10.1002/jpen.1602. [Epub ahead of print].

[125]Pelekhaty S, Galvagno SM Jr, Hochberg E, et al . NitrogenBalance During Venovenous Extracorporeal MembraneOxygenation Support: Preliminary Results of a Prospective,Observational Study[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2018,May 25. DOI: 10.1002/jpen.1176. [Epub ahead of print].

[126]Allen JG, Arnaoutakis GJ, Weiss ES, et al . The impact ofrecipient body mass index on survival after lungtransplantation[J]. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2010, 29( 9):1026‑1033.DOI:10.1016/j.healun .2010.05.005.

[127]Singer JP, Peterson ER, Snyder ME, et al . Body compositionand mortality after adult lung transplantation in the UnitedStates[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2014, 190( 9):1012‑1021.DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201405‑0973OC.

[128]Oshima A, Nishimura A, Chen‑Yoshikawa TF, et al .Nutrition‑related factors associated with waiting list mortalityin patients with interstitial lung disease: A retrospectivecohort study[J]. Clin Transplant, 2019, 33( 6): e13566.DOI:10.1111/ctr.13566.

[129]Jomphe V, Lands LC, Mailhot G. Nutritional Requirements ofLung Transplant Recipients: Challenges and Considerations[J]. Nutrients, 2018, 10( 6). pii: E790. DOI: 10.3390/nu10060790.

后可发表评论

后可发表评论

相关推荐

1

慢阻肺急性加重RICU住院患者的营养管理

4041

2

随堂小笔记 | “重症肺言”之营养治疗专家共识巡讲(北京站)

3812

3

脓毒症营养支持

3710

4

重症患者保护性营养支持策略的临床应用与研究进展

3688

5

随堂小笔记 | “重症肺言”之营养治疗专家共识巡讲(武汉站)

3212

6

随堂小笔记 | “重症肺言”之营养治疗专家共识巡讲(上海站)

3164

7

ARDS俯卧位肠内营养安全性和耐受性评价

3016

8

慢阻肺急性加重期患者肠内营养实施流程

2632

9

随堂小笔记 | “重症肺言”之营养治疗专家共识巡讲(广州站)

1788

10

危重症患者康复阶段的营养补充:关注瘦体重

1170

友情链接

联系我们

公众号

公众号

客服微信

客服微信